INTRODUCTION

Inherited retinal disease (IRD) is a genetically and clinically diverse group of diseases and is the most common cause of blindness in working-age Australians.1 Gene-based clinical trials investigating potential therapies for patients affected by mutations in specific IRD genes are rapidly emerging. Such trials include those for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (PDE6B, RLBP1, MERTK, USH2A), Stargardt disease (ABCA4), achromatopsia (CNGA3, CNGB3), Leber congenital amaurosis (RPE65, CEP290, GUCY2D) and Usher syndrome (USH2A, MYO7A), and for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RPGR), choroideremia (CHM) and retinoschisis (RS1).2

Research is actively pursuing the development of possible therapeutic strategies in cells, tissues and animal models. Research laboratories are developing personalised disease modelling platforms in which fibroblasts taken from a patient are reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells and differentiated into retinal tissues. Access to patient-derived retinal cells harbouring IRD-causing mutations has provided unique opportunities for the investigation of mechanisms of disease and the screening of therapies directed against specific genes or pathogenic variants.3-7 Additionally, in 2017, the first gene-replacement therapy for inherited retinal disease, voretigene neparvovec-rzyl, was approved by the US Federal Drug Administration for treating patients with confirmed bi-allelic RPE65 mutations.8

Availability of genetically diagnosed individuals is an essential requirement for pharmaceutical companies embarking on gene-based clinical trials, and for application of therapies arising from these trials. Additionally, the establishment of a causative gene for a patient allows informed genetic counselling, in particular for family planning purposes. The availability of genetically diagnosed indiviuals highlights cases where syndromic disease may be indicated and is an aid where competing differential diagnoses exist.

In this paper we describe the Australian Inherited Retinal Disease Registry and DNA Bank (AIRDR), a central research repository of DNA and genetic and clinical data for Australians affected with an IRD.

METHODS

Establishment of the Australian IRD Registry

The Department of Medical Technology and Physics (DMTP) at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital (SCGH), Western Australia (WA), provides a state-wide service for visual electrophysiology testing, and is therefore an efficient site at which to recruit IRD participants in WA. A registry of clinical and family information from WA IRD patients was established in DMTP in 1984. In 2001, we began collecting DNA samples from WA participants, and in 2009 we expanded this process Australia-wide.

Ethical and quality assurance

This project was approved by the SCGH Human Research Ethics Committee (Human Research Ethics Committee approval number 2001-053). All activities related to this project were carried out in compliance with DMTP’s ISO9001:2015 quality accreditation.

Participant selection and referral

Participants were recruited from the Retina Australia membership, the SCGH visual electrophysiology clinic, referrals by ophthalmologists, or by responding to unsolicited approaches by potential participants. For inclusion in the registry, participants were required to have a provisional or confirmed diagnosis of an IRD or be a blood relative of a person with such a diagnosis. A confidence level was assigned to each diagnosis depending on its perceived reliability. Age-related macular degeneration, optic atrophy or other non-retinal ophthalmic genetic diseases were not included in the registry.

Structure of the Registry

Details of the components of the registry have been described previously.9 Briefly, demographic details, clinical indicators, family history and pedigree structure for each participant were stored in the registry. Clinical data were either self-reported, obtained from medical notes, or both. Hard copy records were kept in filing cabinets secured within DMTP. Initially, electronic text data were stored in a Microsoft Access (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) database and family trees were documented in a Cyrillic v2.02 (Cyrillic Software, Oxfordshire, UK) database. In 2013, electronic data were migrated to a Progeny version 10.2.0.0 (Progeny Genetics) database.

Biological specimens

Once informed written consent to collect and store DNA was obtained, registered participants were asked to attend their closest accredited pathology collection centre for blood collection (2x10mL; EDTA). Samples were couriered to the AIRDR in accordance with UNN73. Saliva was an alternative source of DNA, and, where appropriate, saliva kits were sent to participants.

Historically, the AIRDR used the WA DNA Bank for DNA extraction and storage as previously documented.9 Since January 2020, the DNA bank at the Lions Eye Institute has been used for this purpose. Blood received by the AIRDR was transferred to the DNA bank, where genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using standard procedures. Extracted DNA was stored at –80°C in two different locations. Historically, a buffy coat was extracted from a third vial and stored at –80°C. With improved DNA extraction efficiency, a third sample is no longer collected. Alternatively, DNA was collected from saliva (2 mL; Oragene DNA self-collection kit OG-500; DNA Genotek, Inc., Kanata, ON, Canada), extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored as described above.

Genetic analysis

Current analysis methods include next-generation sequencing (retinal/ocular gene panels with or without copy number variation (CNV) analysis; whole exome sequencing; whole genome sequencing; single molecule molecular inversion probes (smMIP),10 array comparative genomic hybridisation (array CGH), quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and phase/segregation analysis using bi-directional Sanger sequencing or qPCR. Historical analysis methods included genotyping microarray, bi-directional Sanger sequencing of entire genes, and custom SNP-array followed by haplotype analysis.11 Variant pathogenicity was assessed and interpreted in accordance with the joint guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics & Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology.12

RESULTS

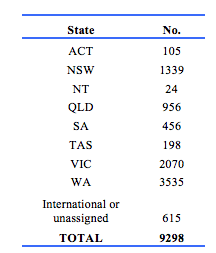

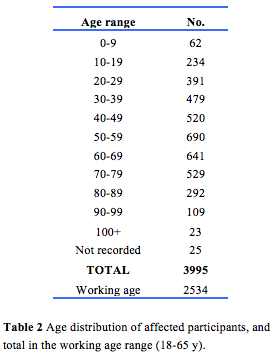

Demographic details of 9298 participants were recorded in the registry. Of these, 4863 were female, 4412 were male, and 23 did not have a gender documented. The distribution by State is shown in Table 1. The high proportion in WA reflects the history of the register. The age distribution including those in the working age range is shown in Table 2. Table 3 gives details of clinical diagnoses and reports issued.

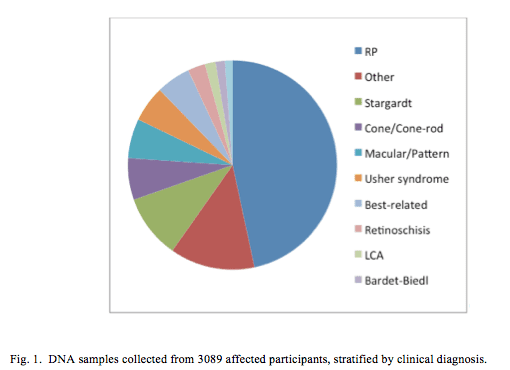

Of the 9298 participants, 4097 (44%) were classified as affected and 1451 (16%) were carriers. DNA was obtained from 7275 (68%) participants (Fig. 1), 3089 (42%) of whom were classified as affected and 1315 (18%) as a carrier.

3995 participants were recorded as being affected and having no date deceased recorded. 3699 were aged 20 or over. Based on genetic analysis of DNA followed by subsequent inspection of bioinformatics data and possibly full pathogenicity assessment, one or more causative variant genes were assigned for 828 affected participants from 491 families (Appendix 1). Each of these cases represents a family affected with Mendelian or mitochondrial disease. Other candidate pathogenic variants have been established but await assessment.

RESULTS

Demographic details of 9298 participants were recorded in the registry. Of these, 4863 were female, 4412 were male, and 23 did not have a gender documented. The distribution by State is shown in Table 1. The high proportion in WA reflects the history of the register.

The age distribution including those in the working age range is shown in Table 2.

Table 3 gives details of clinical diagnoses and reports issued.

Of the 9298 participants, 4097 (44%) were classified as affected and 1451 (16%) were carriers. DNA was obtained from 7275 (68%) participants (Fig. 1), 3089 (42%) of whom were classified as affected and 1315 (18%) as a carrier.

3995 participants were recorded as being affected and having no date deceased recorded. 3699 were aged 20 or over. Based on genetic analysis of DNA followed by subsequent inspection of bioinformatics data and possibly full pathogenicity assessment, one or more causative variant genes were assigned for 828 affected participants from 491 families (Appendix 1). Each of these cases represents a family affected with Mendelian or mitochondrial disease. Other candidate pathogenic variants have been established but await assessment.

DISCUSSION

Research results established by the AIRDR have enabled further development of national and international IRD research and improved patient management, as detailed below.

1. Development of personalised therapies: Appropriate participants in whom we established the genetic cause of disease were referred to the Ocular Tissue Engineering Laboratory at the Lions Eye Institute. Here, fibroblasts were reprogrammed into pluripotent stem cells and subsequently differentiated into retinal tissues carrying the same mutations that exist in the participant. Experiments were then carried out to assess or correct the mutation in vitro, with subsequent analysis confirming that the established mutation was disease-causing, enabling investigation into correcting the mutation in vitro as the basis for future retinal therapies. Pluripotent stem cell lines were established by the Lions Eye Institute for AIRDR participants associated with the genes RP1, USH2A, PRPF31, ABCA4, CRB1, RCBTB1 and CLN3,13-19 with other lines under development. These patient-derived stem cell lines are currently being used in projects aimed at validating variant pathogenicity, elucidating molecular pathogenesis and screening potential treatments, such as gene-replacement therapies and splice-modifying antisense oligonucleotides.

2. Provision of research diagnostic genetic reports: A total of 1037 research diagnostic genetic reports were provided to participants’ ophthalmologists or genetic counsellors. Of these, 704 (68%) reports were provided for affected participants, 678 (96%) of which indicated the probable causative gene. For affected participants, the report diagnosis frequency mainly reflected diagnosis frequency within the registry (Table 3). Diagnoses over-represented in these reports included Stargardt disease (22% reported, 9% in registry), Leber congenital amaurosis (4% and 1%) and choroideremia (4% and 1%). Best disease was the stand-out diagnosis under-represented (2% and 5%).

The 3393 affected unreported participants either did not have genetic analysis performed, had some form of genetic analysis which was not instructive, or were awaiting pathogenicity assessment or report creation. The intention is to establish the causative gene for all affected participants and to report that research finding to participants’ nominated ophthalmologist or clinical genetics service.

These reports significantly improved patient management for many participants. Genetic counselling was provided for family-planning purposes, in some cases facilitating preimplantation genetic diagnosis. AIRDR genetic findings have also alerted clinicians to more sinister syndromic disease that required further clinical evaluation, such as Batten disease, Joubert syndrome or possible Mainzer-Saldino syndrome. Informed patient management enabled more reliable prognoses and unravelled competing differential diagnoses, thereby saving expense, inconvenience, time and possible inappropriate treatment of patients. A total of 475 reports were issued that revealed mutations in genes that were relevant to current clinical trials, alerting participants via their ophthalmologists to the need for routine clinical monitoring of the natural history of disease. This enhanced participants’ opportunities to participate in emerging gene-based clinical trials or to benefit from outcomes of these trials.

3. Establishment of specific cohorts for therapy development: In addition to identifying potential trial candidates through provision of genetic research reports, we also actively engaged with companies researching topically relevant therapies. Collaborations with gene biotechnology companies were formed to establish cohorts for RPE65 gene therapy, novel drug delivery systems and anti-oxidant therapies.

4. Establishing the genetic spectrum of IRD in Australia: Based on an IRD prevalence of 1/2000 (20), we estimate that the registry contains DNA for approximately 25% of IRD-affected Australians (3089/12500). Genetic analysis of this cohort is establishing a representation of the genetic spectrum of IRD in Australia. To date, results have been published for Leber congenital amaurosis,21 retinoschisis22 and choroideremia,23 whilst manuscripts for Stargardt disease, X-linked RP, achromatopsia, Usher syndrome and updates on choroideremia and retinoschisis are in preparation. Numerous other studies24-30 have revealed clinical and molecular aspects of disease in relevant pedigrees or cohorts. This research, which has identified many novel pathogenic variants, facilitates a greater understanding of the genetic aetiology of IRD in Australia, thereby directing research into areas likely to have the greatest impact.

5. Development of genetic analysis tools and methods: The AIRDR has developed or has assisted in the validation of various genetic analysis tools and methods. These include the first clinically validated, high-throughput clinical testing method for X-linked RP, smMIPs analysis in patients with Stargardt disease in whom only one ABCA4 mutation was known,10 a suite of programs to semi-automate pathogenicity assessment and patient reporting32 and a custom SNP genotyping panel for genetic analysis of autosomal recessive RP cases.11

6. Identification of cohorts not related to genetic findings: The AIRDR also contacted appropriate participants required by other researchers for non-genetic research related to visual impairment, including studies regarding lifestyle, attitudes or knowledge of support services for visually compromised people.33,34

7. An information resource: We provided an information resource to many people throughout Australia affected with an IRD and their family members. Some hours each week were spent providing information to participants who were otherwise unable to obtain that information.

8. Literature reviews: Two reviews summarising the state of research in the areas of next-generation sequencing and Leber congenital amaurosis were published.35,36

CONCLUSION

The AIRDR is a valuable resource for identifying genetically-confirmed cohorts of IRD-affected participants for personalised clinical trials or treatments or independent research projects, for elucidating the aetiology of IRD in Australia, and for facilitating significantly improved patient management. The relevance of this resource will continue to increase with the advent of emerging retinal therapies.

Provenance: Externally reviewed

Ethics: Ethical approval was received from the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 2001-053).

Disclosures: No competing interests.

Funding: The Australian Inherited Retinal Disease Registry and DNA Bank is financially supported by Retina Australia. Other financial support was provided by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (grants to FKC: GNT1116360, MRF1142962, GNT1054712, and GNT1188694), the McCusker Foundation (FKC) and the Miocevich Family (FKC).

Acknowledgements: We acknowledge the support of the Department of Medical Technology and Physics, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital and the assistance of the Lions Eye DNA bank and the Western Australian DNA Bank. We thank our participating patients and collaborating ophthalmologists and clinical geneticists.

Corresponding author: Dr John De Roach, Department of Medical Technology and Physics, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Hospital Avenue, Nedlands, WA, 6009 Australia. john.deroach@health.wa.gov.au