Introduction

The prevalence of H pylori (HP) in Australian populations varies between the non-indigenous (15.4 – 30.6%), indigenous (76%) and migrant populations (46.2 – 91%).1-3 HP eradication therapy has a role in the management of peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.4-6 Selection of first-line and salvage HP eradication therapy is guided by local surveillance studies as both primary (obtained from patients without prior HP eradication therapy) and secondary (obtained from patients with at least one course of prior HP eradication therapy) isolate resistance demonstrates significant global geographical variation.7,8 The Australian Therapeutic Guidelines endorses the combination of clarithromycin, amoxicillin and a proton pump inhibitor as first-line eradication therapy, based upon local susceptibility data. In the event of treatment failure, salvage therapies include a fluoroquinolone (most commonly levofloxacin), rifabutin-based triple therapy or tetracycline-based quadruple therapy.9 Historically low rates of resistance to all three of these classes of antimicrobials10,11 has meant salvage therapy selection has not required prior culture and susceptibility testing.4,9

We wished to determine the local (Western Australia) prevalence, including temporal trends, of secondary resistance amongst HP, and to identify host risk factors for fluoroquinolone resistance.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study from 2012 to 2017. This included all patients who had received at least one course of HP eradication therapy, and from whom a HP isolate was subsequently cultured from gastric and/or duodenal biopsy specimens. The material was processed by the Microbiology Department of PathWest Laboratory Medicine (PathWest, Perth WA) at the Royal Perth Hospital (RPH). RPH is a tertiary metropolitan public teaching hospital in Perth, Western Australia.

Cases were identified on the basis of the laboratory log of all isolates for which susceptibility testing was performed. Specimen processing and susceptibility testing utilised standardised laboratory methods.12 The MIC for amoxicillin, clarithromycin, tetracycline, metronidazole, rifampicin and levofloxacin were determined using Etests according to the manufacturer’s instructions (AB Biodisk, Sweden) and interpreted using European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing susceptibility breakpoints.13

For patients harbouring fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates, patient demographics and details of prior HP eradication therapy were extracted retrospectively from patient medical records. For the purposes of comparison, the same information was extracted for twice as many randomly selected patients harbouring fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates.

Statistics

Comparison of demographic variables between groups was assessed by chi-squared test for categorical variables. All statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (v25) and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Ethics approval was obtained from the East Metropolitan Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 154 patients with a median age of 45 years (interquartile range 37-58), of whom 49% were male. Their regions of birth were Australia (n=64, 41.5%), Asia (n=63, 40.9%), Europe (n=11, 7%), Africa (n=9, 5.8%), Middle East (n=6, 3.8%) and North America (n=1, 0.6%).

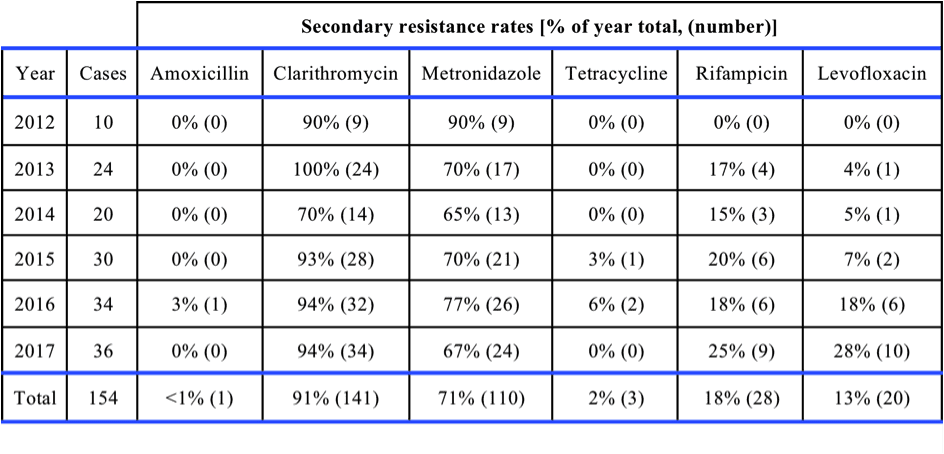

Table 1 provides the rates of HP isolates with secondary resistance to differing antimicrobial classes. There was a significant temporal increase in resistance of HP to levofloxacin from 2012 to 2017 when expressed as the percentage of all isolates with each class of antimicrobial (p < 0.001). As similar trend was not observed with other antimicrobial classes but a late increase in resistance for rifampicin was noted. The MIC50 and MIC90 for levofloxacin over the study period were 0.064 and 4 microg/mL respectively.

Rates of levofloxacin resistance were significantly higher in those born outside of Australia (20/90, 22.2 %) compared to those born within Australia (0/64, 0%; p<0.001). The countries of birth of patients with levofloxacin resistant isolates were China (7), India (3), Russia (2), Afghanistan (2), Vietnam (2), Iran (2), Korea (1) and Sudan (1).

Prior exposure to fluoroquinolones occurred in 13 (65%) of 20 patients with levofloxacin resistant isolates, compared to 5 (12.5%) of 40 patients with levofloxacin susceptible isolates (OR 15.17, 95% CI, 3.9–58.3, p<0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that prior fluoroquinolone use and being born overseas were co-variates (p = 0.024).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that in a collection of Western Australian HP isolates, secondary resistance to fluoroquinolones increased progressively from zero to 27.8% from 2012-2017 (Table 1). This trend may be driven by an increasing number of isolates obtained from patients born overseas. This is a novel risk factor for fluoroquinolone-resistant Helicobactor pylori.

Systematic antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance programs exist in Australia and New Zealand for a wide variety of bacterial pathogens, however these programs do not include HP.14 We are aware of only 1 previous Australian study of secondary resistance to fluoroquinolones.15 Seven years ago, Tay et alfound a rate of secondary resistance to fluoroquinolones of 6%, but no attempt was made to examine temporal trends or risk factors for harbouring fluoroquinolone resistant isolates.

Increasing rates of fluoroquinolone resistant HP are well described overseas.10,16,17 However, in contrast to the Australian setting, this has largely been attributed to increased rates of primary resistance10 which in turn correlates with increased community consumption of fluoroquinolones.18 Due to a policy of restricted access, the Australian community experiences uniquely low usage of fluoroquinolones,14 which is reflected in a recent Australian study demonstrated nil primary fluoroquinolone resistance with HP.19

Several factors may explain increasing secondary resistance to fluoroquinolones in Australia. Firstly, immigration to Australia from neighbouring developing countries, in which there are higher rates of fluoroquinolone resistant HP, is increasing1,15,20 and importation of fluoroquinolone resistant pathogens other than HP has previously been described.21,22 As has occurred overseas,16,18,23 increased use of fluoroquinolone-based salvage therapy is likely to be occurring in Australia as, during the study period, more recent versions of the national guidelines endorsed fluoroquinolone-based salvage regimes9 and levofloxacin availability increased.9 Following fluoroquinolone exposure, stepwise point mutations within the gyrAand gyrBregions leads to an incremental increase in fluoroquinolone MIC24 and prior fluoroquinolone therapy has previously been shown to be a risk factor for resistance to this class of antimicrobial.18,25 Prior non-fluoroquinolone therapy also been shown to be a risk factor for fluoroquinolone resistance in HP, possibly due to co-selection of fluoroquinolone resistance determinants.26

Our findings have important clinical implications. Currently empiric fluoroquinolone-based salvage therapy without prior biopsy for culture and susceptibility testing is endorsed by the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines.9 The major determinant of successful HP eradication is the absence of pre-treatment resistance27 and a recent international consensus statement4 proposed that when clarithromycin resistance rates exceed 15-20%, this class of antimicrobial should not constitute part of empirical HP eradication therapy. By extension, our data suggests that, for a subset of patients receiving salvage therapy, fluoroquinolone resistance may have exceeded this threshold in Western Australia. Thus we believe there may be a role for selective culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing to guide choice of salvage therapy. In the context of HP demonstrating 12% secondary resistance to fluoroquinolones, a recent Italian randomised controlled trial demonstrated this strategy to be associated with significantly higher rates of HP eradication.28 It may also be more cost effective.29.30 On the basis of our and others data, patients who would benefit from this strategy could be identified based upon risk factors for fluoroquinolone resistance such as country of residence7,10,18 or birth, prior fluoroquinolone-based HP eradication therapy and increasing age.5,25

Throughout the study we demonstrated low rates of resistance to amoxicillin, indicating that it remains an appropriate component of fluoroquinolone-based salvage regimes. I n the event that non-fluoroquinolone based salvage therapy is warranted, isolates are (on the basis of our data) more likely to be susceptible to tetracycline than rifampicin, while acknowledging that rifampicin resistant does not necessarily predict rifabutin resistance.31

Our study has several other limitations. Being a tertiary hospital laboratory, there may be a selection bias towards more resistant isolates. HP susceptibility profiles are geographically disparate which may limit the generalisability of our data, and emphasises the need for periodic local surveillance to inform therapeutic guidelines. We did not analyse clinical outcomes and hence we were unable determine the in vivoimpact of fluoroquinolone resistance. We note that fluoroquinolone-based salvage therapy demonstrated 90% HP eradication success rate in the Australian context, although secondary resistance rates were not assessed.19

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that, as with other pathogens in Australia and overseas,14 rates of antimicrobial resistance in HP continue to rise, which has implications for selection of empiric salvage therapy. There may be an increased need for selective culture and susceptibility testing, performed on patients selected based upon risk factors such as prior fluoroquinolone therapy and country of birth.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Ethical approval:Approved by East Metropolitan Health Human Research Ethics Committee.

Funding: Not required

Review: Internal review by TMJ.

Corresponding Author

Dr Puraskar Pateria, Department of Gastroenterology, Royal Perth Hospital, PO Box X2213, Perth, WA 6847, Australia.

Email – Puraskar.Pateria@health.wa.gov.au