Introduction

Research should be one of the pillars of a resilient flexible health system,1 and building research capacity is crucial for maintaining or improving quality of care and patient outcomes. Translational research is an important phase of the research process. Allied Health professionals (AHP) comprise a significant and vital proportion of the Australian healthcare workforce across several professional categories. Such personnel are uniquely placed to design, generate, and execute clinically meaningful research, and translate it into practice.2,3 However, the literature indicates that the research culture within Allied Health is overshadowed by prioritisation of delivery of clinical services, and is hampered by a number of barriers to engagement (such as lack of time, research skills, and resources) despite an interest in conducting research.4-7 Given evidence that the proportion of edAHP either leading or participating in research is limited, an examination of the factors influencing Allied Health research capacity and culture is critical to informing strategies to support research capacity building.4,8

Research capacity building must consider changes at multiple levels within a health care system, including at the level of the individual, professional group, and organisation. There is a growing body of literature examining research capacity within specific Allied Health professional groups9,10 and across AHP as a group.11-13 Frequently, AHP reported a greater degree of confidence associated with preliminary components of the research process (e.g. locating and reviewing relevant studies) and a lesser degree of confidence associated with later stages of the research process (e.g. applying for and securing funding to support research, preparing ethics applications, preparing manuscripts for journals).11,12 At a broader level, AHP have previously reported areas of service strength to be promoting evidence based-practice and supporting publication of research. Relative areas of weakness previously described in the literature relate to provision of resources (funds, equipment, administrative support) and availability of research career pathways.11,12 A multi-systemic evaluation of needs and capacity is, therefore, imperative if meaningful capacity building and support strategies are to be developed to encourage Allied Health research within healthcare systems.

A rigorous assessment of needs, as well as measurement of baseline research capacity and culture is integral to the development of useful strategies to support the development of Allied Health research initiatives. The aim of the present study was to measure perceived Allied Health research capacity and culture within a large metropolitan health service in Western Australia (South Metropolitan Health Service; SMHS). Through the study, we looked to examine research capacity and culture across different settings within the service (e.g. tertiary and secondary hospitals; community-based health care settings) as well as different AHP within the service. Specifically, the study aimed to describe self-reported strengths, areas for development, barriers and motivators to doing research at the level of individuals, professional groups and the organisation itself.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey of AHP within the SMHS. The SMHS comprises five hospitals and several community-based public health services, providing health care to approximately 25% of Western Australia’s population across a catchment area of 3,300 square kilometres. All AHP employed within the SMHS (n = 870) were invited to participate irrespective of employment status (permanent, part-time, casual) or level of seniority. Data were collected electronically via Survey Monkey for five weeks in February and March 2020. Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the SMHS Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: RGS0000003805).

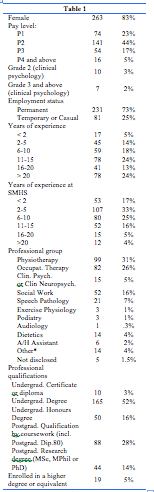

Data were collected on gender, Allied Health professional group, place of employment (hospital or community setting), educational qualification, years of experience (in role and within SMHS), employment status and grade, current enrolment in higher degree studies, participation in common research-related activities, and inclusion of research in one’s role description. All questions were optional and results were anonymous and confidential. Participants had the option not to disclose their gender, professional group or geographical work area.

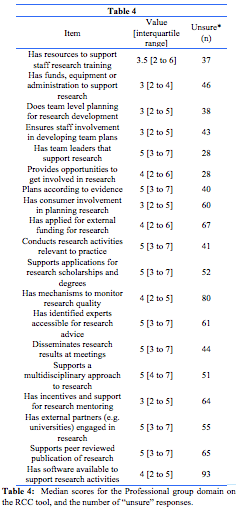

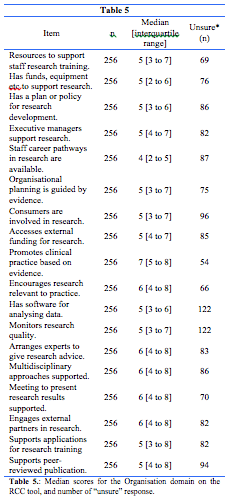

Participants also completed the Research Capacity and Culture (RCC) tool.14 The RCC is a valid and reliable questionnaire that consists of 52 questions examining participants’ self-reported success or skill in a range of areas related to research capacity or culture across three domains: (i) “individual” (15 questions); (ii) “team” (19 questions); and (iii) “organization” (18 questions). For the purposes of the study, “team” was defined as a participant’s professional group. Each question uses a 10-point numeric rating scale format where 1 is the lowest possible level of skill or success and 10 is the highest possible level of skill or success. There is also an option of ‘unsure’.14 Items are scored separately for each domain (i.e. individual, professional group, organisation). The RCC also includes questions regarding participant’s own perceptions of factors that motivate them to conduct research, as well as barriers to undertaking research. In line with previous work,12,15,16 scores for items were further categorised as “low” (median <4), “moderate” (4 – 6.9) and “high” (≥7) success.

Analysis A complete case analysis approach was used for data analysis, with no imputation of missing data. Participants were included in the analysis if they recorded their profession, demographics, and at least one numeric response to the individual, professional or organisation level questions. Those who did not respond, or stated “Unsure” to all answers were excluded. Data collected online from the Survey Monkey platform were exported for analysis to Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were used to express data for demographic variables (mean and percentage of sample). Percentages were used to express results for the categorical motivators and

Results

A total of 331 AHP (38% of those invited) accessed the survey during the data collection period. Of these, 257 completed the entire survey (response rate 77.6% of those who examined the survey). Four did not consent to participate in the survey, seven provided consent but did not answer any of the questions, and 63 incompletely answered the questions. In total, data from 320 AHP were available for analysis (Table 1), representing 37% of the known total Allied Health workforce within the SMHS. The majority of respondents (79%) were employed in hospital settings within the service.

Fourteen percent of respondents (n=44) had completed a postgraduate qualification by research (i.e. MSc, MPhil or PhD). An additional 5% of respondents (n=19) were enrolled in a higher degree by research or other professional development relating to research. Table 2 presents data relating to research engagement and support in the workplace. The majority of respondents stated that research activities either did not constitute part of their job description (42%) or were unsure (26%) as to whether it was part of their job description.

Responses in the RCC are shown according to the three domains:

RCC individual level domain: Table 3 displays responses for the RCC “individual domain”, in which respondents graded themselves against each research skill. Only the item “finding relevant literature” was rated highly (Table 3). The table also shows the number of respondents who were “unsure” of their research skills.

RCC professional group level domain: This domain defined the extent to which a given profession is supported in the undertaking of research. Most items were rated in the range as moderate success. Six items (shaded) were rated as low success (Table 4), and none had a high success rating (7 or greater).

RCC organisation level domain: At the level of the organisation, respondents rated SMHS as highly successful only in the category “promoting clinical practice based on evidence.” All other items were rated in the range of moderate success (Table 5).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess Allied Health research capacity and culture in a Western Australian sample of Allied Health professionals.

Consistent with other samples in Australia,12-15 participants reported moderate to high levels of research success within the SMHS organisation, and scores relating to the success of the organisation trended higher than those relating to the professional group or the individual. For example, the median scores for the Organisation domains “Promotes clinical practice based on evidence” (7 [5 to 8]) and “Encourages research activities which are relevant to practice” (6 [4 to 8]) in the current study are rather similar to the median scores reported in studies performed in urban Victoria13 (8 [5 to 9] and 7 [5 to 8], respectively) and urban Queensland14 (7 [5 to 9] and 6 [4 to 8], respectively). Further, the median score for the lowest-scored Individual domain “Secures research funding” (2 [range 1 to 2]) in our study was equivalent to the two previously mentioned studies (Victoria 2 [1 to 5]; Queensland 2 [1 to 4]).

Bearing similarity to studies conducted in Queensland, Victoria and New South Wales,12-15 participants rated their individual capacity to conduct research as being strongest in domains which relate to preliminary stages of research (i.e. finding relevant literature, critically reviewing the literature, and designing questionnaires). Barriers (e.g. lack of time for doing research; other work roles take priority; and lack of suitable backfill for research) and motivators (e.g. to develop skills, increased job satisfaction, and career advancement) to conducting research are also comparable to those reported by participants in other Australian settings,9,12,13,17-19 suggesting that these findings are likely transferable across a range of healthcare organisations and may be used to inform policy more broadly. Our findings highlight the need for a multi-faceted approach to research capacity building within Allied Health, accounting for strategies at all levels of the organisation’s social-ecology. This finding aligns with previous recommendations for a whole of organisation approach which encompasses a variety of different strategies.20-23

There are myriad benefits to the engagement of AHP in research at the individual, professional and organisational group levels.24-26 Studies have been undertaken to develop research capacity building interventions, forwarding strategies such as protected time and funding for AHP to engage in research activities, mentoring, external partnerships (e.g. with universities), tailored education and training, and the provision of Allied Health research leads or facilitators.4,26,27 These strategies have demonstrated success. For example, Wenke et al28 showed that protected clinician research time influenced clinician research skill and output (e.g. approved ethics applications, grant-funding received, peer-reviewed publications), enhanced workplace research culture, and improved the reputation and profile of Allied Health. These evidence-based recommendations would readily meet the needs of participants expressed in the present study. It is also critical to consider the diversity of interest in undertaking research within AHP. It appears evident from both this study and the broader literature that a stepped model of research engagement has utility, whereby some professionals lead and actively participate in research, other less experienced and/or interested staff assist with the research process (e.g. data collection, recruitment of patients), and all professionals become skilled in using research to guide their practice.26,29,30 Accordingly, research capacity building interventions should be targeted to the needs, interests and goals of specific individuals and teams, rather than a ‘one size fits all’ approach. The findings of this study will be used to inform the development of tailored interventions in collaboration with key stakeholders from each professional group within SMHS, in order to enhance existing motivators, mitigate barriers and build upon current skill levels. For example, some proposed strategies include: creating opportunities to participate in research (e.g. assisting with collecting data; pairing novice researchers with more experienced research mentors within the same and/or other teams/organisations); building and maintaining partnerships with other health services and universities; and maintaining a register of current and future research ideas. Research registers have previously been proposed as a means of identifying research interested individuals, consolidating similar projects, facilitating linkages and measuring changes in research capacity over time (i.e. tracking numbers of projects in progress).31,32

This study has strengths and limitations. Data from 320 AHP were available for analysis, representing 37% of the known total Allied Health workforce within the SMHS. This is a higher response rate than many other studies using the RCC tool.8,12,13,16,32,33 However, the 37% response rate refers to the 320 participants who provided at least some information. Between 256 and 320 individuals responded to individual questions/domains. Lower response rates were detected in questions located towards the end of the questionnaire, suggesting that some AHP may have dropped out before reaching the end of the online survey). This can be described as survey fatigue or burden, which has been reported previous study that used the RCC tool.17 Of note, our sample captured professionals from a broad range of settings, including acute and rehabilitation settings within a major tertiary hospital, non-tertiary hospitals, and several community settings. However, findings must be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. Given the 37% response rate, it is possible that self-selection bias may affect the results, whereby research interested clinicians were more likely to take part in the survey. However, this bias is consistent with other studies which have used the RCC tool, therefore our findings are likely comparable to others. Further, although valid and reliable, the RCC is a self-report tool that measures attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge of health professionals. Regarding research success, data collected via the RCC tool may not correlate with objective research activity and output.32 Future efforts to elucidate research capacity should consider multi-modal data collection which includes other objective measures (including traditional output measures such as number of peer reviewed publications, conference presentations, grant funding awarded and research qualifications, as well as more sensitive process measures such as number of successful ethics applications, number of research and quality improvement projects underway).19

Conclusions

Our results highlight the need for multi-faceted Allied Health research capacity building programmes with strategies matched to individual, professional group, and organisation levels of the health care system. Given the enormous potential for good quality Allied Health research output, initiatives should capitalise upon known motivators to conducting research, and use evidence-based practices such as protected time and allocation of resources to overcome common barriers to research engagement in Allied Health. The steps that are being introduced at SMHS to improve Allied Health research capacity and culture include, but are not limited to: (i) providing opportunities for AHPs to get involved in research projects; (ii) optimising access to information, research education and training; (iii) developing research mentoring structures and processes; and (iv) building new collaborations and strengthening existing collaborations with academics. Steps that are under discussion are: including research in role descriptions and establishing protected time for research within work hours; establishment of research career pathways; and recruitment and recognition and of staff who engage in, lead and facilitate research.

Provenance: Externally reviewed

Disclosures: None

Ethics approval: Not required

Corresponding author: Dr Vinicius Cavalheri, Allied Health Research Director, South Metropolitan Health Service, Locked Bag 100 PALMYRA DC, Western Australia 6961, Australia. vinicius.cavalheri@health.wa.gov.au