Introduction

Scabies and discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) are common dermopathies affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia.1–3 Scabies is an often-neglected disease caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, an ectoparasitic mite with high disease prevalence in the tropics, especially in low-income areas.2 DLE is the most typical form of chronic cutaneous lupus and is also highly prevalent in these populations.3,4 Dermatopathic lymphadenitis is a paracortical lymph node hyperplasia secondary to chronic dermopathies, which may be inflammatory, infective, or neoplastic in origin.5,6 DLE and scabies are often clinically diagnosed, but histopathology can support equivocal presentations. In addition, simultaneous pathologies can further confuse histopathological interpretation, posing a diagnostic challenge. We present a case of dermatopathic lymphadenitis secondary to DLE and occult scabies. The patient presented with unusual symptomatology of generalised pruritus, B symptoms (fever, night sweats and weight loss), lymphadenopathy, and unexplained hypereosinophilia with disseminated depigmented plaques.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old female Aboriginal patient from a remote community in Northern Western Australia [Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia Plus (ARIA+) = 5] was referred by her general practitioner to a tertiary emergency department. She had a 2-year history of worsening generalised pruritus, skin lesions as below, unexplained chronic hypereosinophilia (5.27 × 109/L), and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (116 mm/h). She described symptoms of lassitude, anorexia, and unintentional weight loss over the last three months preceding her hospital presentation. The past medical history was significant for previous scabies, hypertension, stage G3b A1 chronic kidney disease secondary to presumed hypertensive nephropathy, and osteoarthritis.

Fig. 1: Well-circumscribed atrophic plaques scattered along the patient’s arm, with central depigmentation and circumferential hyperpigmentation.

On examination, she had Fitzpatrick VI skin with depigmented plaques on her arms and limbs. Secondary excoriation was seen (Figure 1). No stigmata of scabies, such as mites, burrows or nodules, were found. There was a sizeable confluent and reportedly enlarging area of depigmentation on her forehead (Figure 2). A possible rheumatic cause for her presentation was not identified: rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative, as were tests for hepatitis B and C, HIV, tuberculosis (by Quantiferon® test) and Strongyloides infection. Extractable nuclear antigen test was positive for Ro52 and Ro60, but there were no sicca symptoms, and salivary gland ultrasound was normal, suggesting Sjogren’s syndrome was not present. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses were elevated for IgG1 29.14 (normal, 3.82-9.29 g/L), IgG3 2.25 (0.22-1.76 g/L), and IgG4 1.54 (0.04-0.86 g/L), suggestive of a non-specific infective or inflammatory process.

Fig. 2: A large, confluent plaque of depigmented skin with islets of normal skin and irregular borders on the patient’s forehead and frontal scalp, measuring approximately 7.5 × 8 cm.

These findings did not meet the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology entry criteria for a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus, due to negative ANA titres. The widespread rash was suspected to represent DLE, but the generalised pruritus, chronic hypereosinophilia, and raised ESR remained unexplained by DLE alone.

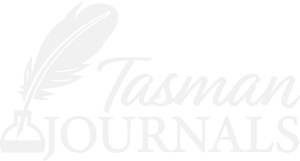

Skin biopsies were taken from the depigmented plaques on the patient’s arm and back. Histopathology revealed orthohyperkeratosis with irregular acanthosis, parakeratotic follicular plugging, an interface change with apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer, and a moderate superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and abundant admixed eosinophils (Figure 3).

Fig. 3: Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of skin biopsies were obtained from the patient’s arm and back. Orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis overlying the epidermis with moderate to florid irregular acanthosis and underlying superficial and deep inflammation (A, x20 H&E). There were areas of follicular plugging and interface change (B, x20 H&E). Post-inflammatory pigment alteration is evident, with pigment-laden macrophages in the superficial dermis (C, x100 H&E). While the changes are otherwise quite typical of discoid lupus erythematosus, the additional presence of eosinophils within the inflammatory infiltrate (D, x400 H&E) is not a typical feature of that condition.

These findings were mostly in keeping with known histopathological features of DLE, except for the superficial and deep inflammatory infiltrate with abundant eosinophils (Table 1). No spirochetes or pathogenic fungi were seen in immunohistochemistry or periodic acid-Schiff staining, respectively. A dual diagnosis of DLE and occult scabies was suspected despite the absence of direct visualisation of scabetic mite body parts or mite faeces.Ivermectin (spaced oral dosing of 200 mcg/kg on day 1 and day 7) was commenced as anti-scabies therapy. For DLE, the patient was prescribed thrice daily betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment wet-wrap therapy for both limbs and methylprednisolone acetate 0.1% ointment to her forehead twice daily. The pruritus resolved with both treatments, and the hypereosinophilia and inflammatory markers became normal. The depigmented plaques did not resolve with acute topical corticosteroid therapy, but improvement in that respect had not been expected because of the chronicity of these lesions.

Subsequent radiologic workup of the B-symptoms revealed fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid nodes in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal stations, similar to the changes in lymphoproliferative disorders. FDG-avid cutaneous foci were also seen, which was consistent with DLE. No evidence of a solid organ malignancy (Figure 4) was found. The patient underwent an axillary lymph node core biopsy, revealing normal lymph node architecture with sinus histiocytosis andmelanosis. These findings culminated in a final diagnosis of dermatopathic lymphadenitis complicating combined scabies and autoimmune DLE.

Fig. 4: The patient’s positron emission tomography scan showed widespread low-grade cutaneous foci visualised throughout the imaged torso, most apparent in the vertex and posterior scalp. Fludeoxyglucose-avid nodes are also seen in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal stations.

As the patient remained asymptomatic during outpatient follow-up, systemic therapy for DLE was not commenced. She was advised to avoid sun exposure and apply tinted sunscreen for cosmesis and sun protection and continues to be reviewed regularly in the outpatient setting to monitor for any changes in her condition.

Discussion

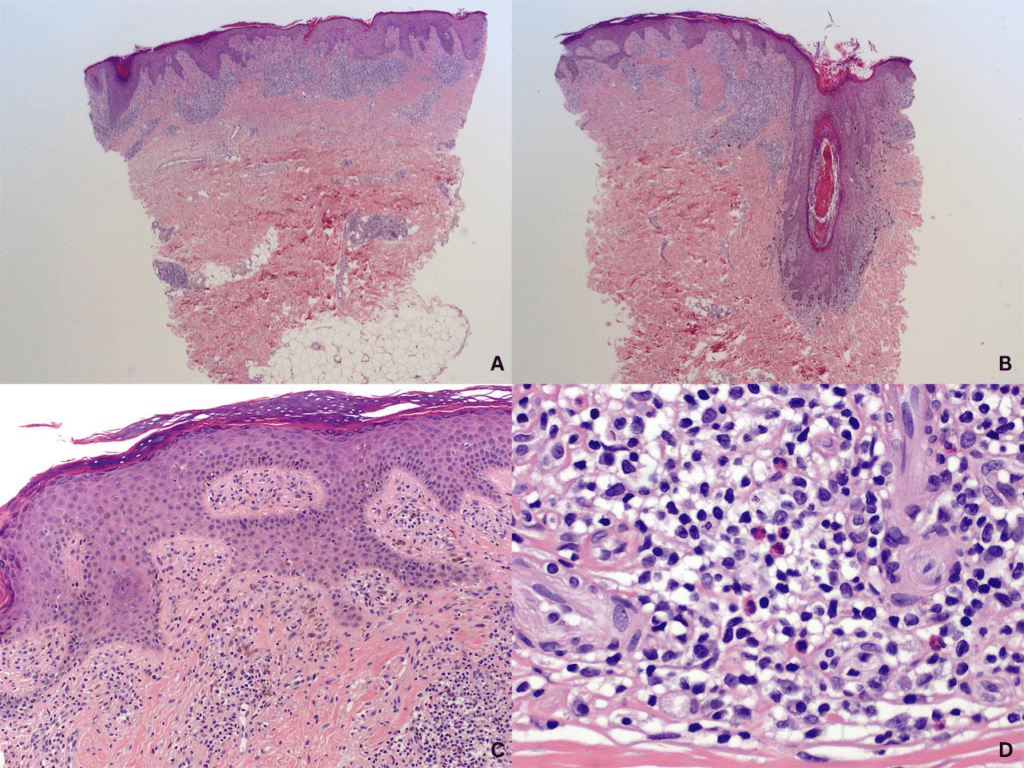

Discrete DLE or scabies presentations may be diagnosed clinically or supported with typical histological findings, as summarised in Table 1.2,7–9 Eosinophilia is not typically seen in DLE. The patient’s mixed histological findings, with typical features of DLE but with the additional presence of abundant eosinophils, raised the possibility of a dual diagnosis of DLE with occult scabies. Her demographic background as an Aboriginal Australian from a rural community is significant, as scabies has a high prevalence in such populations but is often neglected. The presence of pruritus and the patient’s symptomatic and biochemical response to ivermectin further supported the presence of occult scabies.

Dermatopathic lymphadenitis is a histological diagnosis of exclusion, as the lymphadenopathy and constitutional symptoms can mimic malignancy.5,6,11 While it is uncommon, the risk is increased when the prevalence of potentially causal diseases is high. Both DLE and scabies are highly prevalent in Aboriginal people. The reasons are not well-studied, but they are likely to stem from multiple factors that include genetic susceptibility, increased environmental ultraviolet radiation exposure, chronic bacterial or parasitic infection, poor social circumstances such as overcrowded housing, and decreased access to health services. The latter includes specialist dermatologic care.2–4,12 The high prevalence of DLE and scabies underscores the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of skin diseases in such populations. In our patient’s case, the chronic 2-year history of DLE and probable occult scabies underpins the need for improved access to specialist dermatologic care. Barriers can be categorised into geographical factors that affect all rural patients and cultural factors which are more pertinent to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients.13

There are significant financial and time-related costs involved in transporting medical and nursing staff to remote locations.13,14 Furthermore, there are added difficulties for patients accessing regional health centres, which may be hundreds of kilometres away. Cultural and linguistic barriers exacerbate these logistical challenges, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients may not speak Standard Australian English as their first language.14 These factors in combination delay diagnosis and treatment and in consequence increase complication rates.13,14 While solutions such as telemedicine and asynchronous ‘store-and-forward’ consultations have reduced geographical and logistical challenges, further workforce and infrastructure reforms are required to overcome the barriers.12,14

This case illustrates the importance of considering the possibility of concurrent scabies and DLE in Aboriginal patients with pruritus and hypereosinophilia, and in treating scabies empirically, even in the absence of classic scabetic signs. Histopathology in concomitant DLE and scabies may present with atypical findings that can complicate diagnosis. It is also prudent to screen for B symptoms and assess lymphadenopathy in patients with chronic dermopathies, as the cause may be haematologic malignancy rather than secondary dermatologic lymphadenitis. Our case underscores the importance of considering overlapping histological features in diagnosing dermopathies. In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients living in remote communities with a high disease burden of chronic dermopathies such as DLE and scabies, an awareness of dermatopathic lymphadenitis is essential.

Provenance: Externally reviewed.

Statement of financial support: No external funding support

Competing interests: None declared

Acknowledgements: None.

Corresponding Author: Dr Tristen TW Ng, Department of Dermatology, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth WA 6000 Email: tristen.ng@uwa.edu.au