Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a mental health diagnosis in which patients present with dysregulated emotions and impulses, self-destructive or self-injurious behaviours, chronic suicidal thoughts, unstable interpersonal relationships and an unstable sense of self.1 Due to these symptoms, patients with BPD can experience recurrent emotional and interpersonal crises in which they feel overwhelmed, are unable to think rationally or solve problems, self-harm, and have suicidal thoughts or actions.2 During such periods, patients with BPD commonly present to hospital emergency departments (ED) seeking the support and safety provided by an acute inpatient mental health admission.3

Based on evidence of clinical and cost-effectiveness, the UK National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) released (in 2009 and 2012 respectively) clinical practice guidelines for the management of BPD.4,5 The guidelines recommend that the majority of a patient’s treatment should be provided by community-based mental health services, given the strong research outcomes for the efficacy of longer-term outpatient-based psychological therapy for BPD.4,5 A combination of expert opinion and sparse research outcomes indicate that extended inpatient treatment is not beneficial and may be countertherapeutic.6

Despite these recommendations, patients with BPD are one of the highest users of tertiary inpatient psychiatric services and emergency department services.3,7-9 Seventy two percent of these individuals require hospitalisation and represent 25% to 30% of all psychiatric admissions.10 Furthermore, chronic suicidality, sensitivity to rejection and abandonment, and poor ability to self-manage further crises, often results in delayed discharge from mental health units, extended hospital stays or a reliance on tertiary care with repeated re-presentations through emergency departments.11-12

Best practice guidelines emphasise that when an inpatient admission to a mental health unit is clinically indicated by high risk of suicide or significant self-harm, the admission should be brief.4,5 The usual recommended maximum is three to five days.2,13 Involving the patient in decision-making around admission is crucial to reducing potential risks of inpatient care, such as loss of self-determination and responsibility.14 Furthermore, a collaboratively agreed crisis admission plan where the patient is involved in the decision minimises the need for patients with BPD to escalate their disordered behaviour in order to communicate the significance and seriousness of their distress to clinicians and increase the likelihood of inpatient admission.15-16 A recent study of patient-initiated brief admissions in adults found that patients reported a significant decrease in anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as improved health-related quality of life between admission and discharge.17 There is also evidence to suggest patient involvement fosters more collaborative relationships between mental health staff and patients and reduces work-related stress for staff.18,19

A point of difference between some other crisis plans in the literature and PCAP lies in the direct involvement of the patient when a crisis arises.20 In many settings, clinicians retain control over admissions due to limited experience in relinquishing control, ongoing fears of the patient’s ability to manage clinical decision making around their care, concerns about overuse of resources and the lack of specificity in clinical guidelines on how patient engagement in clinical decision-making should be achieved. Research on the effects of crisis admissions on hospitalisation rates in patients with BPD is limited and suggests either no changes or a reduction in total number of days in inpatient care and fewer days in involuntary care.21,22 The data suggests that the healthcare system should enable patient determination in the activation of the plan when in crisis to seek a brief inpatient stay/admission for containment and co-regulation of emotional distress/crisis.

Patient-controlled brief admissions have thus far been implemented and evaluated primarily in an adult population. Sweden is the only other country known to us to have evaluated a crisis admission model in adolescents with BPD traits.23 Initial evidence suggested that adolescents perceived brief admissions as a helpful alternative to managing self-harm urges including attempted suicide, although some also found the responsibility challenging and were concerned about not being able to abstain from self-harm, this being a requirement for admission.23 Application of the model for a youth population up to 24 years aligns with achievement of neurological maturity and behaviour, including developing responsibility and autonomy, at ages beyond adolescence.24 It also assists young people requiring ongoing treatment, and future transition to adult services. The development and implementation of a Patient Controlled Crisis Admission Plan (PCAP) for youth patients with BPD is designed to develop patient empowerment, prevent deterioration, and assist with discharge and ongoing patient management.

Methods

Fiona Stanley Hospital (FSH) Mental Health Youth Unit

The FSH Mental Health Youth Unit (MHYU) is a 14-bed inpatient unit that provides comprehensive assessment and treatment of young people aged 16 to 24 years who are experiencing severe episodes of mental illness that cannot be managed in the community. A significant proportion of admissions and readmissions are patients with emerging or diagnosed BPD. Extended inpatient admissions are unhelpful for this population,5 and the service was developed to provide a new model of care aimed at providing a safe, consistent therapeutic environment where the patients can access the support and interventions required during an acute relapse. The MHYU opened in 2015, and the PCAP model of care was developed over the first two years of inpatient admissions. These plans facilitate an inpatient admission for up to 72 hours for identified youth patients presenting in crisis to a youth mental health unit in Australia.

Patient Controlled Crisis Admission Plan (PCAP)

The PCAP enables a patient with BPD to access an inpatient admission for up to 72 hours during times of distress or increased risk of harm and where previous coping mechanisms have had limited outcome or could not be deployed. The admissions are always voluntary and usually at the patient’s discretion, although their community team may have recommended an admission. There is no limit to the number of admissions and no minimum time between admissions. The target population for PCAP is primarily youth in the age range 16-24 y with BPD or BPD traits. PCAP has also been used in patients with a history of extended hospital admissions or dependency on inpatient services and who may have related diagnoses such Histrionic Personality Disorder, Dependent Personality Disorder and Conversion Disorder. PCAP exclusion criteria are Antisocial Personality Disorder, alcohol or other drug dependency issues for which the patient is declining treatments including withdrawal management, and significant intellectual or cognitive deficits. The PCAP was trialled iteratively in 2015 and 2016, with the current model in place since 2017.

Aims and Goals of PCAP

The main aim of PCAP is to provide a safe and consistent process to access crisis containment and support during an acute exacerbation of symptoms, including increased risk of self-harm or suicide. Patients with BPD often feel disempowered in regulating their own experiences, as well as the way in which they relate to others. The plan encourages patients to develop responsibility for monitoring their personal health needs as well as promoting healthy help-seeking behaviour and building emotional skills and self-efficacy for coping. The PCAP is geared towards assisting the development of collaborative and trusting patterns of relationships with health care providers and decreasing escalating behaviours by reducing the patient’s perceived need to amplify distress through self-harm, suicidal behaviours and substance abuse to access support. Patients are encouraged to utilise their PCAP before self-harming or attempting suicide. With less escalation required for admission, the patient may be more quickly ‘contained’ by emergency department and ward staff. This allows focus on pre-identified strategies intended to reduce distress. By providing a PCAP as an ongoing commitment, we provide an alternative experience of hospital presentation that does not reinforce their often-held negative view of the world as rejecting, unpredictable, uncaring and untrustworthy, and of themselves as worthless, undeserving and a failure. The consistency of support from the same or consistent clinicians encourages the patient to maintain stable community supports and decreases dependence on acute care.

The PCAP is accessible on the Psychiatric Services On-line Information System (PSOLIS), a WA state-wide electronic information sharing system for all patients treated by a mental health service. This system helps to ensure that the care provided and the willingness to provide it is consistent across WA. The PCAP is also important in assisting patients to feel less resistant to discharge because they know it remains an ongoing, available option.

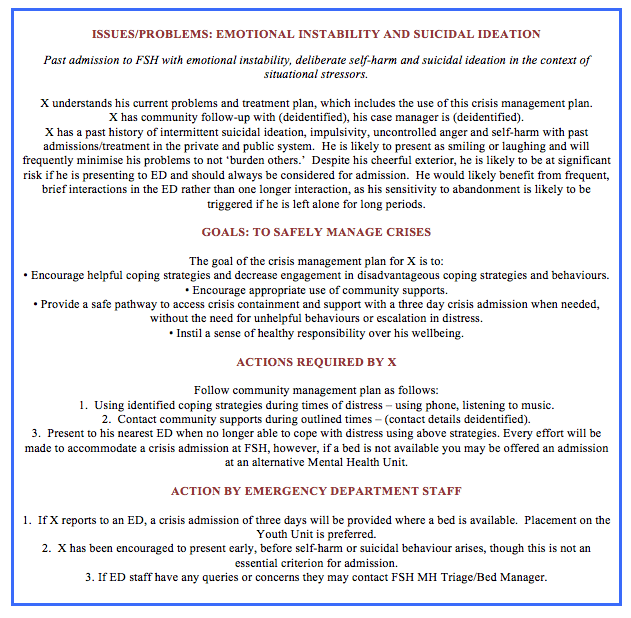

Process of Providing a PCAP

The development of a PCAP for an eligible patient begins during the initial admission, which typically lasts for up to two weeks. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) assessment is conducted. This includes input from psychiatry, clinical psychology, occupational therapy, community support teams and nursing, as well as social work, dietetics and neuropsychology as required. The initial admission ensures that an accurate diagnosis is made and that the young person is taught to engage therapeutically with the team. The decision to provide a PCAP is discussed with the patient, their family or carers, and within the team. When agreed, the plan is developed by the allocated clinical psychologist. The PCAP will outline the diagnosis, summary of presentation, the plan for managing future mental health crises, process for accessing a PCAP, information for ED staff on how to support the young person prior to admission, and recommendations for any future crisis admissions to hospital (see Box). In order to ensure the individual will seek community supports they are required to be engaged with an external support service such as community mental health, private psychiatrist, clinical psychologist or general practitioner, or be willing to be referred to such a service on discharge. A copy of the PCAP is distributed to the patient community services, carers or family, and uploaded to PSOLIS. The PCAP is reviewed annually or as required by the allocated clinical psychologist in discussion with the MDT.

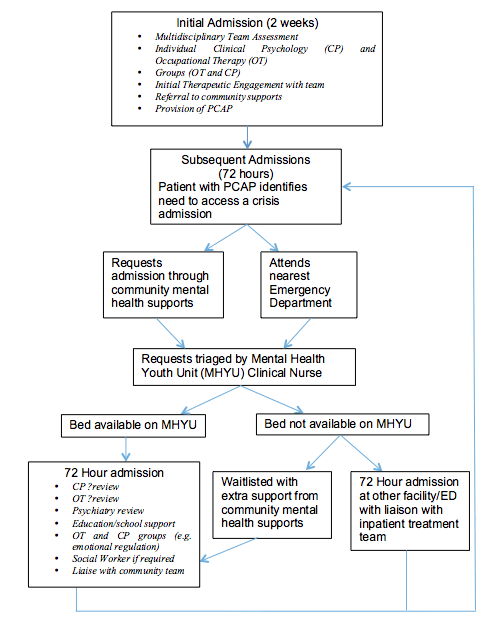

Accessing a PCAP

When a patient decides they need to access their PCAP they have two options (Fig. 1). The first is to contact their community support and ask to be referred for a PCAP admission. The second option, if the patient believes their current risk is high or their level of distress is severe, is to present to the nearest Emergency Department. This decision remains with the patient. The MHYU Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) triages requests from community supports or the Emergency Department and if required arranges admission, which depends on bed availability. If no beds are available in the MHYU the patient can choose between the options of being admitted to another unit, completing the 72-hour admission in the Emergency Department or being placed on a waitlist for a MHYU bed with additional support in the community meantime.

PCAP Admission in MHYU

On admission to the MHYU, the patient will be reminded that the admission will be for a maximum of 72 hours. If possible, the same treating team manages the case across admissions. The admitted patient will see members of the MDT including their assigned Clinical Psychologist if available, Occupational Therapist or Psychiatrist, and will attend therapeutic groups on the ward. The groups are intended to develop skills in emotion regulation, distress tolerance and interpersonal relationships, which are key therapeutic targets for patients with BPD. The chosen or nominated community services and family are contacted to be advised on progress and to co-ordinate discharge planning. Family meetings during admission are arranged as required. Early discharge may occur when the patient believes their crisis is contained and expresses a readiness to be discharged, or if they break standing ward rules, for example harm another patient or use illicit substances.

Results

Demographic information and healthcare utilisation data was collected for all patients admitted to MHYU using a PCAP between July 2017 – June 2020 (n = 389 PCAP admissions and 99 patients). The mean age was 18.3y (range = 16 – 23y). All patients were either diagnosed with BPD, BPD traits or had a history of extended hospital admissions with evidence of dependency on inpatient services to regulate their care. Co-morbid diagnoses included adjustment disorders, anorexia nervosa and post-traumatic stress disorder. The average length of hospital stay was 2.7 days (SD = 0.9, range = 1-7). Sixty-nine of the 99 patients did not access their PCAP for more than a year. In the 30 patients who used their CPAP over several years, admissions decreased in 80%.

Individual Case Study

We report this successful case without claiming that the system is successful in all patients.

Patient A was initially referred to the MHYU at age 16 and met DMS-5 criteria1 for BPD. She had been in government care from the age of 14, had no family support and a background of physical and emotional abuse and abandonment. She had refused ongoing community treatment support, apart from a WA government Department of Child Protection case worker. She had a significant mistrust of others, a negative view of herself and her worth, and engaged in chronic self-harm and suicidal behaviours. After her first two-week admission she was assigned a PCAP. She had 6 further admissions in 2015 (average LOS 4.0 days), and 5, 5,.5 3 and 4 admissions in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019. The LOS from 2016 to 2019 were 2.6, 2.2, 2.3 and 2.3 days. There were no admissions in 2020.

This patient reported in writing as follows: “The MHYU has been an important protective factor in my recovery. With having the ability to access admissions when things are too tough, the ward has helped me gain trust in professionals and has been crucial and consistent support, and for someone with a background like myself, consistency was something I was lacking…The unit has been such a stable support to lean on when I was at risk and as each year I am accessing them less and less and noticing such a change… (it) ensured that I had a constructive plan so that my mental health treatment wasn’t spread over numerous hospitals, but instead would access an environment that I was familiar with. The youth unit offered help with making sure I had the community support I required and was there when that all fell through.”

During the period of community engagement under the CPAP, this patient finished high school, completed a university bridging course, has maintained accommodation and is currently in her third year of a university degree.

Limitations & Risks of the Model

Lack of bed availability risks deterioration of a patient while waitlisted for PCAP admission. The patients are informed of bed pressures when provided a PCAP, as well as efforts to prioritise access to PCAP admissions, to help set realistic expectations. Collaboration with the community team and the option to present to ED helps manage the risk of escalation if no beds are available in MHYU. Additionally, the PCAP model, by providing a recognised admission pathway, can facilitate patient flow from the emergency department to MHYU.

Some mental health units cap the number of brief admissions to avoid overdependence and overuse of inpatient resources.13,23 Our PCAP model does not limit the number or time between admissions. It recognises the individual may have periods of greater and lesser need for inpatient stays depending on an array of environmental factors. The risk of more frequent admissions is weighed against the risk of escalation of self-harm or suicidal behaviour implicit in an admission cap.

The current model differs from a Swedish model for adolescents that made brief admissions conditional on no self-harm or suicidal behaviour.23 In our model, the young person is encouraged to access PCAP as an alternative to self-harm or suicidal behaviour, but this is not a requirement for admission. The admissions reduce the severity or frequency of maladaptive behaviour, and reduce the risk of punitive or shaming responses to self-harm.

Patients with BPD tend to organise the way they relate to the world by idealising service providers they perceive as validating and supportive and devaluing services that cannot immediately meet their needs.25 Hence a patient’s idealisation of the inpatient unit is a risk of our model. To minimise the potential for this ‘splitting’ dynamic between services, the model of care promotes collaboration and continuity between patient’s inpatient and community teams.

Discussion

This paper describes a new model of care for engaging with young people with BPD in an acute psychiatric hospital inpatient setting. It builds on advice in national guidelines for inpatient treatment of BPD.4,5 Our recommendations for brief and fewer readmissions over time empowers the individual and minimises their subjective rejection from health care services.4,14 Attempts to avoid inpatient stays for people with BPD may be experienced by the patient as invalidating and rejecting, whereby they believe their problems are unworthy of admission. The PCAP model of care maintains a commitment to understanding and responding to a patient’s emotional distress and crises, and validating their need for mental health care while promoting their connection to a life outside of hospital via community supports. There is increasing recognition of the benefits of brief patient-controlled admissions in other countries,13,20,26,27 including a current large-scale implementation in Sweden that includes a child and adolescent clinic.26

The model also incorporates essential elements of brief admissions for BPD outlined in the literature review by Helleman et al,28 including admission goals discussed with patient prior to utilisation, a written treatment plan, an admission procedure that is well understood by all, clear descriptions of interventions used, and conditions for premature discharge made clear.23,27

Our preliminary data suggest strong adherence to the model of care. Average LOS was less than 3 days, suggesting that the model facilitates early discharge for these patients. LOS was extended for some patients due to treatment of comorbid diagnoses or barriers to discharge such as unstable accommodation. This highlights the need for collaboration with community services. About a third of patients utilised their PCAP for more than a year and initial evidence suggested that frequency of PCAP admissions reduced over time for most patients. The individual case vignette above demonstrates the potential benefits of the PCAP model

This model suggests that brief patient-controlled admission plans may be implemented within a youth population in whom BPD traits often first emerge. It aligns with their developmental needs of autonomy and responsibility and may reduce the risks of long-term dependency on inpatient mental health care. A unique aspect of this model is that it has been effected in a real world setting in which patients have complex psychosocial and mental health difficulties, intermittent engagement with services, and co-morbid diagnoses. Other current research investigating a similar crisis admission plan excluded those without community outpatient psychiatric care or in unstable housing, which includes many of the patients we treated under PCAP.13 Further research to assess the longitudinal patient and service impacts of implementing brief patient-controlled admissions in adolescence and early adulthood is indicated.

Our PCAP model of care is consistent with NHMRC and NICE guidelines4,5 and offers a consistent and apparently effective way of providing brief inpatient admissions for patients who would present repeatedly to hospital emergency departments or are sub-optimally engaged with community psychological therapies. Preliminary data and our subjective experience is that the PCAP system reduces admissions, lowers length of stay and encourages connection with community mental health supports. We will undertake a formal analysis of the service data to confirm these clinical impressions.