Background

Nearly 2 million Australian adults are initiated on a prescription opioid each year, and this is increasing annually.1 Similar patterns have been observed in North America2 and Europe.3 This increase in prescription is associated with opioid misuse, overdose, dependence, diversion4 and opioid-related deaths.5,6 A large proportion of opioid prescriptions are for management of chronic pain. Oxycodone is the drug most commonly prescribed.7

Emergency Department (ED) clinicians routinely manage acute painful conditions with a range of analgesic options. The use of opioid analgesia for acute trauma including fractures, is part of guideline recommendations.8 However, there are many conditions that have limited evidence for opioid prescription, such as headaches,9 chronic pain, and soft tissue injuries.10

Patients with acute pain due to trauma or surgery are less commonly at risk of continued opioid use than patients with chronic pain.11 However, this does not negate the importance of ensuring appropriate prescribing for patients with acute pain presentations. Regardless of the indication, the number of days of opioids prescribed is the most influential prescribing factor in determining their continued use.11 Other factors positively associated with increased long-term use include age, female sex, previously diagnosed mental health disorders, and concurrent prescription for hypnotics or muscle relaxants.11,12

We conducted this study to inform implementation of pathways and interventions to optimise acute pain management. It describes opioid prescribing practices in ambulant patients with acute upper limb fractures presenting to two Queensland emergency departments.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a retrospective descriptive study in ambulatory patients with upper limb fractures in two EDs in Southeast Queensland. The first ED is part of a tertiary public hospital and level 6 trauma centre and the second is within an urban district hospital. In 2018, the two Departments had an estimated combined total of 158,254 presentations.13 The two departments serve the Gold Coast area of Queensland, which has an estimated population of 592,330. Both hospitals have orthopaedic services and use the same electronic medical records (EMR) system. The medical staff work across both sites. The local Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study. The reporting of this study adheres to STROBE guidelines.14

Participants

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years or older and presented to the either ED and were diagnosed and discharged with an upper limb fracture within 7 days of sustaining the injury. Patients were excluded if they were admitted to hospital, re-presented to hospital following an initial presentation, had multiple injuries or neurovascular compromise, presented more than 7 days after the injury, or did not have sufficient information in the medical records.

Data collection

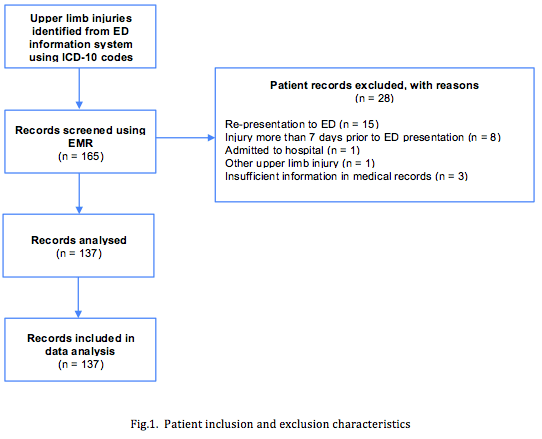

Patients were identified using the Emergency Department Information System (EDIS). Medical records of patients with a diagnosis of an upper limb fractures as indicated by the relevant International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes (S42.40, S42.3, S42.20, S52.20, S52.4, S52.50, S52.8) between 1 January and 28 February 2019 were reviewed (Figure 1). Relevant variables were collected from the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) using a preformatted data collection sheet. Patient histories, medication charts, prescription forms and other medical notes were reviewed for the variables shown in Table 1. Further detail is available on request from the Corresponding Author. Pilot data collection on 20 patients was undertaken independently by two researchers (RH/VD). This information was compared for concordance, to ensure inter-rater agreement. In case of disagreement, a senior researcher (GK) was the arbiter. Of the variables where discordance occurred, two related to the primary outcome of interest (dosage of opioid prescription). Following this, minor changes were made to the data dictionary for the variables collected, and subsequent data extraction was performed by a single data abstractor (RH and VD both reviewed half of the medical records).

‘Simple analgesia’ was defined as medications available over the counter without prescription. The morphine milligram equivalents (MME) variable used the conversion factors specified by The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists.15

Sample size and data analysis

As this was a descriptive study, a formal sample size was not calculated. Based on an expected opioid prescription rate of 35%, a sample size of 137 would provide an estimate with an error margin of +/- 8%. Data were analysed using SPSS and descriptive statistics were reported. Categorical data were summarised using percentages and confidence intervals, and continuous normally distributed data was summarised using mean and standard deviation. Difference in proportions were tested using Chi square analyses.

Results

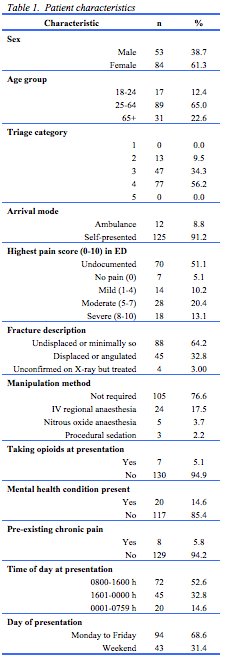

A total of 137 unique patients were eligible and included for analyses (see Figure 1). Characteristics of the included patients are reported in Table 1.

Demographics

More patients were female (n=84, 61%), and less than a quarter (n=31) was over 65 years of age. Almost two-thirds (64%) of these ambulatory patients had fractures classified as undisplaced/minimally displaced and 8.8% (n=12) were brought in by ambulance. Around one-quarter (23.4%) of patients had fractures requiring manipulation. Pain score was not documented in 51% (n = 70).

Opioid prescribing

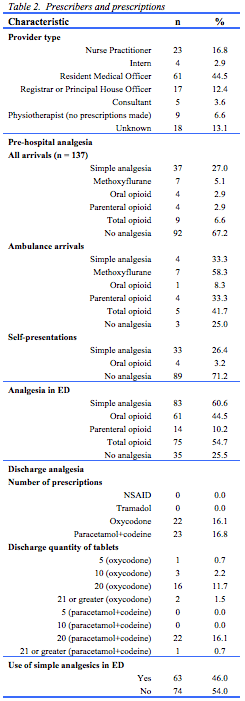

Most prescribers were resident medical officers (45%), nurse practitioners (17%) or registrars (12%). There were no differences in prescribing practices in ED or at discharge between medical prescribers and nurse practitioners (Table 2).

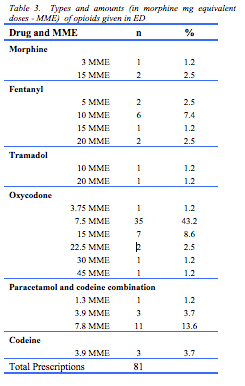

Nine patients (6.6%) received pre-hospital opioids, and over half (n=75, 54.7%) received an opioid in ED. Forty-four patients (32.1%) received a discharge prescription for an opioid prescription of which half were oxycodone (n=22, 16% of total cohort). Of these, 18 received a prescription for 20 or more tablets. Table 3 provides information about the types and quantities of opioids and morphine milligram equivalents (MME) prescribed in ED. The most commonly prescribed opioids were oxycodone (58%), followed by codeine and paracetamol combination (18.5%) and fentanyl (13.6%).

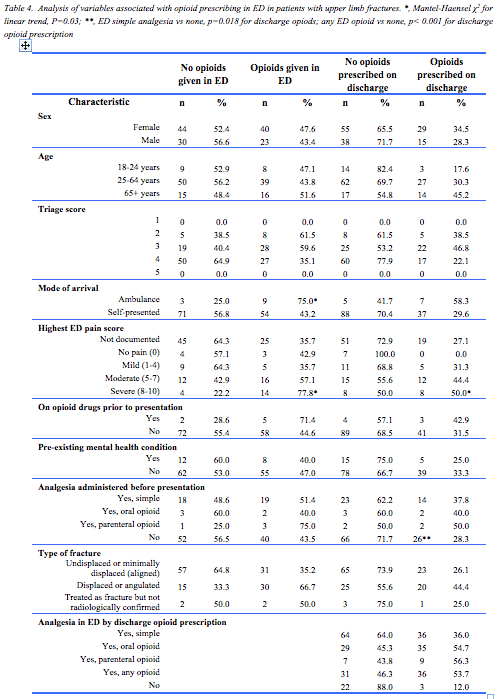

Table 4 provides characteristics associated with prescriptions of opioids in ED and on discharge. Almost half (44%) of the 32 patients requiring manipulation received an opioid on discharge, compared to less than a third (29%) of the 105 who did not require manipulation. Nearly all patients in both groups that were discharged on opioids (90% and 100% respectively) received a prescription of 20 or more tablets. In addition, patients were more likely to receive opioids at discharge if they had received an opioid in the ED (OR: 8.5; 95%CI: 2.3-31.2). There were no statistically significant associations between other patient or prescriber characteristics and opioid prescription in ED or at discharge.

Seven patients were on regular opioids prior to presentation. These patients were usually prescribed simple analgesia in ED (5 of 7) and/or an opioid (5 of 7), and three of these patients (43%) received a discharge prescription for an opioid.

Broader pain management

Just over half (n=74) of patients had simple analgesia pre-hospital, with 60% receiving simple analgesia in ED. Some patients who did not receive any opioids in ED were prescribed opioids on discharge (n=9). Additionally, despite not receiving any simple analgesia in ED, five patients received oxycodone on discharge and 11 patients received codeine and paracetamol combination on discharge. In over half of patients (54%), simple analgesia was not documented as part of discharge management.

Discussion

This study provides insight into opioid prescribing practices in adult ambulant ED patients with upper limb fractures. Over half of patients were prescribed opioids while in ED (54.7%) and almost one-third received a prescription for opioids on discharge. Of these discharge prescriptions, 41 out of 45 (91.1%) had a default prescription of 20 tablets or more.

Although there is more to pain management than opioid prescribing, our study provides contemporaneous data on acute upper limb fracture pain management. Opioid stewardship for (acute) pain includes several other principles beside appropriate opioid prescribing.12 Other pain management strategies include the use of simple non-opioid analgesia, non-pharmacological pain management and patient education and counselling. Many patients who are healthy and opioid naïve may require limited or no opioid analgesia.

Our discharge prescription rate of 32.1% is similar to a recent study in a Victorian tertiary hospital ED where 23.3% received an opioid prescription on discharge with a lower proportion of patients receiving the maximum quantity of opioid (55% vs 91%) compared to our study.16 As they included a broader group of medical and surgical patients, some of the difference may be explained by the difference in study population.

Current discharge prescribing at the study sites often included maximum quantities. Ideally a prescription is optimally tailored to the needs of the individual. Although appropriateness of prescribing was not assessed, it seems clinicians did consider the individual in front of them as higher pain scores and increased severity of the fracture requiring manipulation were associated with higher prescribing rates. State-based ED discharge analgesia prescribing guidelines recommend tailored prescribing, with the prompt that quantities of greater than 10 should be discussed with senior clinicians.17 Similar guidelines exist overseas with the United States’ Centres for Disease Control, who also state that a supply for 3 days or less should be sufficient.18 Shah et al. found that the number of days’ supply of opioid analgesia was the most influential factor for continuing use beyond use for initial indication.11 Another study observing oxycodone discharge practices at a Queensland tertiary hospital ED found the mean total number of tablets prescribed to be 16.7.17 This is similar to our findings, although upper limb trauma injuries accounted for only one-third of the presentations in that study. Furthermore, an educational opioid stewardship intervention targeted at prescribers in that hospital produced a decrease in the mean number of tablets prescribed from 16.7 to 10.7. This is consistent with a large cohort study in Canada, which found that patients who presented to ED with an acute painful condition took on average 10 of their prescribed tablets of 5mg oxycodone in the first 2 weeks after discharge.19 These findings suggest there may be an opportunity to implement tailored opioid stewardship interventions in our setting. Such interventions will benefit from top-down initiatives with institutional and clinical leaders endorsing and promoting appropriate practice by creating awareness (staff education sessions, posters) and promoting resources such as the managing pain and opioid medicines resources developed as an initiative of NPS MedicineWise.20

In this study, prescribing practices varied depending on the severity of the injury. The proportion of discharge opioids was high when intravenous regional anaesthesia, nitrous oxide or procedural sedation was used (83%, 100% and 100%, respectively), where one-third of patients with undisplaced fractures received a discharge opioid prescription.

More females were prescribed opioids on discharge than males (34% vs 28%). Differences in pain experience between sexes have been described,21 as well as higher risk of long-term opioid use in women.11,22 However, such differences do not mean less opioids should be prescribed to women, but rather suggests there is scope to explore other sex-specific pain management strategies.

An association between age and the proportion of individuals prescribed opioids on discharge was noted, with one in six (17.6%) of 18-24 year-olds and almost half (45.2%) of those 65 and older receiving an opioid discharge prescription. This is of importance as older individuals are at higher risk for long-term opioid usage, adverse events such as constipation and are more likely to have impaired renal and hepatic clearance which require dose modification.11,23

Importantly, in over half (54%) of patients, there was no documented recommendation for simple (over-the-counter) analgesia as part of management on discharge. This was consistent with Stanley et al. who reported that less than half (40.5%) of patients were provided a discharge summary outlining simple analgesia advice and opioid weaning.16 This is an important part of pain management as the use of non-opioid analgesics should be maximised before prescribing opioids for acute pain and must be continued as adjunct to taper opioid use.23,24 Advising simple analgesia is a component of opioid stewardship and it is possible it was adhered to, but not documented, by the clinicians in this study. A recent literature review suggests that nonopioids could be a feasible alternative to opioids for management of acute pain in the ED as it is effective, safe, and decreases the need for rescue analgesia.25

Use of treatment protocols given as written information on discharge may ensure counselling regarding pain management to become standard, particularly for non-opioid and non-pharmacological analgesia. Further investigation into practices surrounding patient analgesia education on discharge may provide improved insight into current pain management.

Limitations

This study is purely descriptive. While undertaken in both an urban and tertiary ED setting in the same health service district, the results may not be generalisable. Experience of pain is subjective and variable as it depends on numerous factors. Thus we are unable to comment on whether the opioid prescribing observed is appropriate. To achieve a relatively homogenous population we studied only ambulatory adults with acute upper limb injuries. We were also unable to examine generally factors possibly associated with decisions in pain management. For example, data on functional activity scores, possible risk of adverse events such as constipation, patient agreement with analgesia and the nature of education and counselling provided to patients were not routinely recorded. We suggest that a future prospective study should include these variables to allow judgement regarding the appropriateness of prescribing.

The study was also subject to limitations associated with medical record review. To reduce the impact of these limitations, we used a pre-formatted data collection sheet. Data extraction was independently conducted by two trained members of the research team and pilot data collection ensured consistency and accuracy of data collection. As concordance was high after the pilot testing of 20 patients, we did not formally calculate inter-rater reliability.

The studied relied on the assumption that medical records were created accurately by prescribers, and absence of documentation was taken as absence of such a variable. This may have caused underestimation of certain estimates, such as the provision of simple analgesia. Important variables such as medication details were generally well documented as part of electronic prescribing, as was the type of fracture, as stated in the radiology report.

CONCLUSION

Opioids were prescribed in most ambulant ED patients with upper limb fractures, and about one third received opioids on discharge. Implementation of relevant guidelines, particularly surrounding the appropriate quantity of opioids supplied on discharge and inclusion of simple analgesia as part of pain management may further optimise care. Opioid prescription is only one aspect of pain management and other strategies be included in future studies to optimise patient-tailored prescribing.

Provenance Externally reviewed

Ethical approval: Approved by the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding: None

Corresponding author: Prof Gerben Keijzers, Department of Emergency Medicine, Gold Coast University Hospital, Southport, Queensland 4125, Australia. Email: Gerben.keijzers@health.qld.gov.au